There are a lot of difficult problems to solve in this course, so

students sensibly use the most practical and familiar methods to do it.

This often involves carrying numbers throughout a long solution. The

following scenario illustrates the advantages of using symbols

(variables) rather than numbers.

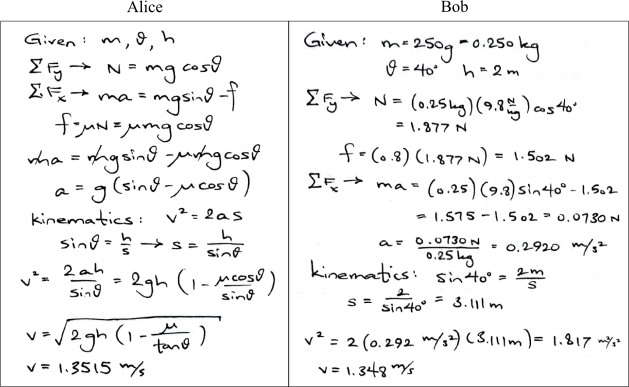

Alice and Bob, both good students, have different ways of solving

Physics problems. Let’s compare their approaches as they confront the

problem shown below.

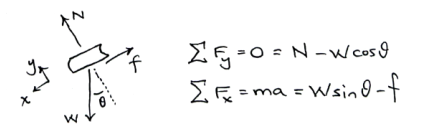

They both begin with a free body diagram and Newton’s 2nd Law.

But from this point Alice proceeds symbolically while Bob sticks with

numerical values.

They both got the right answer, but there are several important

differences.

- Alice is done sooner, spending much less time at

her calculator.

- Alice is less likely to make a mistake. On each

line it’s easy to check her algebra. She may use dimensional analysis as an additional quick

check. For example when she finds acceleration, it reasonably appears to

be a dimensionless factor times \(g\).

Bob had to carefully copy each number from his calculator, potentially

introducing a hidden error, and he cannot check his result without

re-doing it.

- Alice understands more. She sees that book’s mass

doesn’t matter -– the answer applies to any mass. She sees that if \(\mu=0\) (frictionless ramp) then \(v=\sqrt{2gh}\), which she might recognize

as the velocity after free-fall. She notices the interesting fact that

the analysis fails when \(\mu>\tan

\theta\) (not steep enough to slide). She can see relationships

like the fact that a ramp of twice the height would yield a velocity

only \(\sqrt{2}\) times faster. If she

wanted she could produce a graph of final speed vs. ramp angle. Bob,

unfortunately, can do none of these things.

- If the final answer were incorrect, Alice would have a much easier

time finding errors. Anyone could quickly scan her

solution for misapplied theory or algebra mistake, but would have to

walk through every step of Bob’s work with a calculator.

- Alice’s symbolic solution works with any unit

system. Her final equation is true in metric or imperial or any

other units. For Alice, units only appear on the last line as she goes

to the calculator. Bob has to make sure his units are right at every

step.

- Alice can go back later and understand what she

did. All her equations are there to see. She might be able to re-use one

of her intermediate results in a later problem, or use this work to

study from.

- Even though Bob kept four significant digits, round-off

error has accumulated in his solution. His answer is incorrect

in the third digit. This would be greater problem if he kept only 3

digits, or if the problem had more steps, or if an intermediate result

were squared or exponentiated, which compounds the error.

- If Alice wanted to compare solutions with another

student who was given \(\mu=0.7\), she

could easily do so. Bob would have to re-do the entire problem.

- Alice’s algebra skills get stronger with each

problem. Poor Bob develops tendinitis in his calculator finger.

Of course the method you use is up to you. Some combination of

numerical and symbolic work may suit you best.

If you use the symbolic approach, you might consider these tips:

- Assign symbols to input data, including units. Then use these

symbols in your solution.

- If the equations get complicated, define intermediate variables for

expressions that keep reappearing. Pro tip: if the variables you define

are dimensionless, your equations will be easier to check and

their physical meaning will often be clearer.

- As you work, keep track of which variables have known values and

which are still unknown.

- Use a computer to do the calculating. For example, write up the

symbolic solution in a Jupyter

Notebook. Save the code for double-checking, re-use and

sharing.

Last modified: March 30, 2025